All good things must come to an end – goodbye to the land that measures Gross National Happiness So, here we are in Phuentsholing, in a hotel that is literally ON the Bhutan-India frontier, ready to cross the border tomorrow morning (although that plan may be curtailed as there is a tea planters’ strike in West Bengal, and transport is currently blocked). Our time in Bhutan has been an absolute delight. The flight into the spectacularly situated international airport at Paro was an experience in itself (described in the previous post), followed immediately by a visit to a magnificent medieval dzong (fortress), then the sighting of the long sought-after Ibisbill on the river just below our hotel, all of which made for an impressive first day. The next morning saw us leave the hotel at 04.30, spy a probable Spot-bellied Eagle Owl in the bus headlights, and then wind our way ever higher through seemingly endless oak and pine forest to the Chelela pass, at 3988 m, which we reached just as dawn was breaking, and where we were treated to the sunrise illuminating the 7320 m Himalayan giant of Jomolhari. Just below the pass, on the descent towards the precariously perched settlement of Haa, we were privileged to observe both Himalayan Monal and a group of perhaps ten Blood Pheasants skulking through the frosted scrubby vegetation, neither of which are easy birds to find.

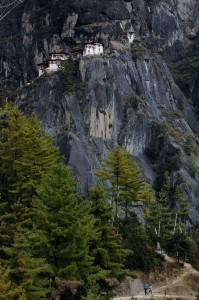

The afternoon excursion was to the Tiger’s Nest monastery, perched in an almost impossibly precarious position on a sheer cliff. Most members of the group made it right up to the site itself, but my very delicate internal condition meant that I was feeling distinctly under the weather and I was forced to turn back in search of sanitary facilities (which I did not find).

The dramatically situated Tiger's Nest

The dramatically situated Tiger's Nest

From Paro we headed eastwards, crossing the Dochula pass and then descending into the next valley to the small town of Punakha, where we commenced a search for perhaps the rarest (and largest) birds of the trip, the White-bellied Heron, Ardea insignis, which is second only to the Goliath Heron in size. The White-bellied Heron’s only known site in Bhutan has been destroyed by the construction of a dam, and the very few birds have moved up river and now frequent the rocky riverbed, where they have now belatedly received full protection. Nobody knows the precise world population of this species, which occurs sparingly around North-east India, Bhutan, Burma and Bangladesh, but it may not exceed 200 individuals. Our scanning for herons was interrupted early on by the sight of a group of eight or nine Otters fishing and performing underwater acrobatics just below us, which kept us entertained for quite some time. We were unable to ascertain whether these were Common or Smooth-clawed Otters as they were precisely on the altitude boundary of where the two occur, and the visual distinguishing features are minuscule.

The otters put on a splendid show

The otters put on a splendid show

One member of our team, Adrian, has perhaps the sharpest eyes of any naturalist I have ever encountered (indeed he has been teased about having a Tibet list as well as a Bhutan one!), and needless to say it was Adrian who spotted the first heron; these enormous birds are extraordinarily hard to find on the rocky islets in mid-river, as they stand motionless among the stones, their subtle grey and white colours blending in with their surroundings.

The White-bellied Heron may be large but it is well camouflaged

The White-bellied Heron may be large but it is well camouflaged

We finally went on to see three of these splendid birds, and it was heartening to know that efforts are finally being made to give them a chance in this ever-developing world, a development which has now reached even the formerly isolated kingdom of Bhutan, which makes stringent moves to protect its magnificent forests and environment, but which is also fragmenting crucial habitats through road and dam construction. The next day saw us working our way up the beautiful Punakha valley on a rough road, stopping at suitable-looking spots and checking the forests for birds. The rice-fields, now either already harvested or soon to be so, were glowing an orangey-brown colour in the morning sunlight, interrupted here and there by traditionally-styled farmhouses (all buildings in Bhutan, whether old or new, conform to the traditional Bhutanese style, with ornately carved wooden window-frames, walls painted with Buddhist motifs, and a pitched roof set up off the actual flat roof of the house itself, providing a space through which the wind can pass and dry crops or newly cut hay). Then began a series of four consecutive days of immensely long drives, something I think the planners of this tour could have avoided, but our first port of call could not have been omitted, the remote Himalayan settlement of Gangtey, in the Phobjika valley. This high, cold area plays host to another almost mythical bird, the Black-necked Crane. Breeding way up on the Tibetan plateau and in Ladakh, a flock of these elegant creatures fly over the high Himalaya to winter here. As we descended into the valley, we were offered the choice of either hiking through the forests to a crane-viewing point or remaining with Rosemary in the bus, stopping on the way to the hotel to look for cranes from the other side of the valley. I found myself in two minds; the hike sounded good, especially after being cooped up in the bus as it powered its winding way up the immensely-scaled Himalayan mountain roads, yet the thought that Rosemary might see the cranes and I might miss them was a worrying prospect indeed! Nevertheless, I did opt for the hike. Our route took us steeply down through pine forest, over a rushing stream and then along the valley side, with occasional gaps in the trees offering views down across the marshy valley floor, but I became more and more worried by the silence. My experience of cranes is that they can normally be heard from a long way off, bugling with their evocative calls that can carry for miles; here the silence was ominous. I need not have been so concerned, however, as a sudden cry of “Whoa!” from our guide Kartikeya Singh brought us all to a standstill, and there, way down in the valley, was a group of perhaps thirty Black-necked Cranes peacefully feeding in the evening sunshine. Considerably larger than the Common Crane, these birds appear grey in the books, but in reality they seem much paler, appearing almost white, with contrasting black “bustles” (cranes appear to have bushy tails, but these are in fact long, curved wing feathers which hang over the tail when the birds are at rest).

Our first group of Black-necked Cranes, a bird I had long hoped to see

Our first group of Black-necked Cranes, a bird I had long hoped to see

A further scan revealed several more groups of birds dotted across the valley, and we were treated to a long and wonderful viewing of these very special birds, accentuated by a beautiful male Hen Harrier (spotted by Adrian!) quartering the grasslands just beyond, his pale grey colouring with jet black wingtips matching that of the cranes perfectly. We were out early the following morning, wrapped up against the icy cold, and were treated to a further sighting of two adult cranes with their two young; seeing these birds through the mist as they strode through the frosty grass, and then watching them as they winged their way off to their daytime feeding grounds elsewhere in the valley, with Oriental Skylarks flitting around us, was a fitting finale to an all-too-short visit to this magical spot.

The Black-necked Crane family winging their way off to feed

The Black-necked Crane family winging their way off to feed

We then retraced our long and winding way out of the Phobjika valley, over a high pass, then right the way down the next valley, over the river near the dam that had displaced the White-bellied Herons, then up and up to the Dochula pass again, before finally descending into Bhutan’s diminutive capital, Thimphu, where we had a look around the slightly shabby but nonetheless interesting centre, before checking into our hotel for the night. The following morning, we were pleased to have the chance to see a little more of Bhutan’s capital, this time from the slopes above the “city”, where we visited a huge gilded Buddha that is under construction on a high bluff overlooking Thimphu, apparently shipped as a kit from Hong Kong. The views of the town were spectacular, as was the extraordinary creature we visited in a breeding centre next, the highly improbable-looking Takin. This extraordinary mammal, something like a cross between a goat, a cow and a pony, is Bhutan’s national animal. It breeds in the alpine meadows of a small area of Bhutan, descending in winter to the more sheltered forests, but this beast is now endangered by road construction and competition from domestic yaks, and is extremely hard to see in the wild. Here at least one has a chance to wonder at this bizarre creature, and hope that its wild cousins can continue to exist in an ever-developing future.

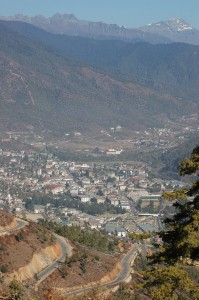

Bhutan's capital Thimphu seen from the new Buddha

Bhutan's capital Thimphu seen from the new Buddha

The rest of the day was again spent in the bus, as we descended ever lower towards Phuentsholing, the steamy, bustling border town, where we are spending one final night in the Land of the Thunder Dragon, a unique land that cut itself off from the corrupting influences of the outside world for so long, only opening itself to “mass” tourism a few years ago, and only passing from an absolute to a constitutional monarchy in 2008. Our very good humoured and ever-smiling guide Jotschu said rather feelingly “We preferred it when the King made all the decisions.” Perhaps that sums up Bhutan, a land that really is different from any other country that I have visited so far – long may that difference remain.