In the beginning

JJW having pulled GCC out of the muddy pool, they started to chat about GCC’s find, and finally JJW invited him back to his home and gave him a clean set of clothes for the train journey back to London. While at the Walkers’ home, GCC was introduced to JJW’s sister Adelaide, who 15 years afterwards became his wife, and later my great grandmother. So, it is fair to say that my very existence is thanks to a humble weevil! The words of JJW sum up the story best:

‘Encouraged by his friend the late Mr J. Platt Barrett, as well as by the award of a small insect cabinet as a school prize, he began, as is so often the case, by collecting moths and butterflies; but his attention was soon engrossed by the Order to which his life-work was devoted, and the splendid collection of British Coleoptera which he amassed in after years was commenced by him when a youth of not more than sixteen … It was during this early period of his work that a chance meeting on the sea-wall near Sheerness, one sunny June morning in 1870 – a day marked by the addition of Baris scolopacea to the British Beetle fauna – initiated a friendship which was cemented fifteen years later by a happy marriage into the writer’s family, and has endured unbroken and unclouded for upwards of fifty-seven years’.

Entomologists’ Monthly Magazine, 63, 1927, pp.197-203

The courtship between GCC and Adelaide Walker took many years to come to fruition, at first because Adelaide’s destiny was to stay at home to look after her aged uncle, and marriage was supposed to be out of the question for her. In addition, GCC’s four years of Central American insect collecting occurred in the meanwhile, and it was not until he returned from Panama in 1883 that he finally felt ready to make a move. He was also adamant that he should have a steady income and be able to offer Adelaide some security before courting her in earnest.

The letters between the two of them offer touching and sometimes revealing insights into their lives and the mores of the times. Her letter to her future husband of 5th May, 1885, begins:

“Dear George,

This is the first time I have ever called a man, other than a relative, by his first name. How strange it feels……..”

Although I had always been aware of this extraordinary, insect-related background that I have, it was only relatively recently that I began to investigate it more thoroughly. In the early Spring of 2008, I made an appointment to visit the Coleoptera (beetle) collections of the Natural History Museum in London. Anyone who has visited this magnificent Victorian building will be aware of the splendid dinosaur skeleton that dominates the entrance hall, the Diplodocus. I had asked beforehand where I should wait for someone to come and pick me up, and the answer had come: “Meet me under the tail of the Diplodocus”. A more appropriate place for the great grandson to meet one of the guardians of his great grandfather’s legacy, just below the plaque commemorating my great grandfather’s employers, Godman and Salvin, could hardly have been found!

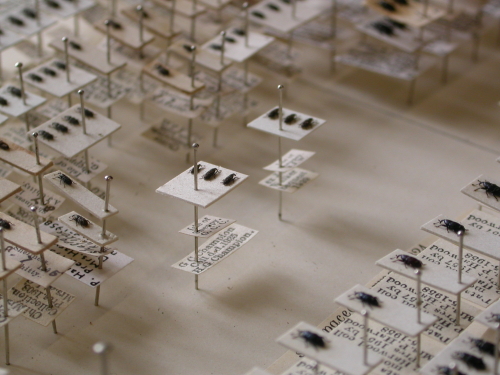

The beetle collections were housed in a temporary gallery suspended beneath the ornate ceilings of the museum, tucked away from public view, and as soon as we had opened the doors, we entered a different world. The entomologist guiding me then called down the corridor, “Lads, there’s a Champion here!”, and suddenly, from between the rows of metal and wooden insect cabinets, entomologists appeared, to greet the great grandson of GCC, who on his death had bequeathed most of his collection, amounting to more than 500,000 specimens, to the museum. A large proportion of the drawers now contain his specimens, even the tiniest beautifully mounted on card, and many labeled with the minuscule but highly distinctive handwriting of my great grandfather, GCC. And they are still in constant use today. Looking at his photograph on the wall, I thought how pleased GCC would have been.

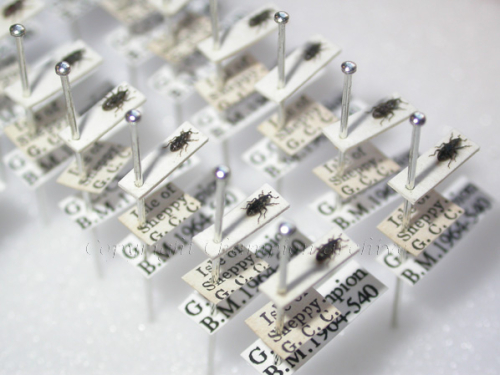

Shortly afterwards, one of the entomologists whispered to me, “Now, young Mr Champion, I would like to show you something rather special”. He took me to a particular cabinet, slowly opened a drawer containing some particularly tiny beetles with a long down-curved snout, all labelled “Isle of Sheppey, June 1870, G C Champion”. These were the very specimens of Baris scolopacea, collected on the sea-wall by my great grandfather, and thanks to which I exist.

Sometimes it is uncanny how stories can come full circle. Following the initial interest in its discovery, Baris scolopacea was not recorded again in the UK (perhaps GCC and JJW had collected all the individuals, leaving none to breed!?) until 1996, when one of the specialists looking after me that day in the museum, Dr Roger Booth, organised a trip to the very spot where it had been discovered in 1870, and was delighted to find that it is still there and still thriving. And just recently, I was being shown around the insect collections of the Oxford Museum of Natural History, and we came across more of the specimens that GCC and JJW had collected. The circle was complete!