GCC's time in Chiriquí draws slowly to a close, and he attends a wild fiesta with locals in the remote mountains In this letter, my great grandfather George Charles Champion displays his frustration at not being able to get on his way eastwards towards Panama City. In those days the overland route was almost impassable so almost all traffic went by sea, but as there were no steamships on these coastal runs, sail had to be relied upon. The area above Tolé, Peña Blanca, etc, where he attended the wild festival with the locals, is still remote and difficult to access. In fact, it is astonishing how empty the landscape of eastern Chiriquí and Veraguas provinces is to this day. George's matter-of-fact writing style conceals the astonishing bravery of the man, travelling alone or with his Guatemalan negro servant Leopoldo, by mule, through this wilderness.

Forested coastal swamps in eastern Chiriquí

Forested coastal swamps in eastern Chiriquí

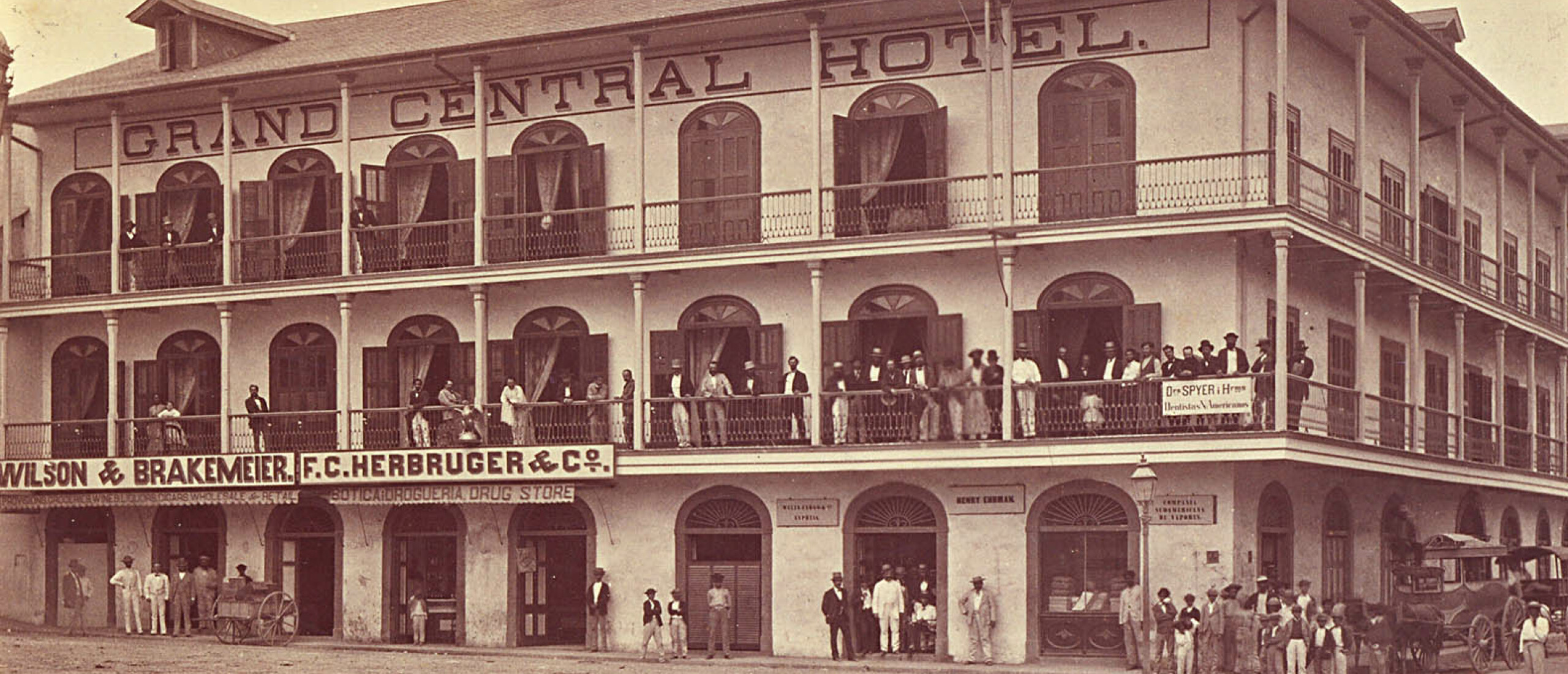

DAVID March 6th 1883 My dear Mother, I am still detained here, waiting for a sailing vessel to take me to Panamá (City), but hope to get off in a few days; there is a small vessel here now, called the “Catalina”, but goodness knows when she will be ready to start. At this season, the winds are so strong, and hurricanes frequent, that I should not wonder at all if we take ten days or a fortnight to get to Panamá, then I shall have the same trouble over again to reach the Pearl Islands owing to the contrary winds; the weather is splendid (if one can stand the heat) but the dust is awful, doors and shutters banging (windows you don’t find in these countries) every moment, tiles blowing off, and the coconuts bend with the wind but they do not break) but almost a cloudless sky since Christmas, and scarcely a drop of rain. I would rather remain a few months longer than return in the winter, especially as London has few if any attractions for me (except to see you all again) at the present time. I doubt if I will ever be able to get used to the noise and bustle again, having lived so long in the wilds, of course you know that I never liked London, and during my four years absence in the tropics, my dislike has increased tenfold. This letter I shall send by land; if I had my own way I would not start for any journey by sea for another month yet, but as I have been so much delayed from one cause and another, and as I ought to have been in Panamá by the end of December, I must start at the first opportunity. You can have no idea how uncertain and slow everything is in this country, there is not the slightest certainty about anything, the people never hurry themselves, it is always “tomorrow” and when tomorrow comes, it is the day after. During my last journey to Tolé, Peña Blanca etc, I was fortunate enough to be able to go to the annual gathering of the Indians of the district, held at a very solitary, out-of-the-way place in the mountains. There were about 300 Indians, men, women, and children present, many from places very far distant; they came with their faces hideously painted, red and black, the men wearing straw hats full of feathers, and most of them carrying a stuffed puma or other animal on their backs, women bare-headed, painted like the men, and with a long dress like a coloured bedgown from the shoulders to the heels; this dress they wear quite loose, not tied at the waist, and they cut their hair short all round alike and comb it down over their eyes, but Oh! so dirty, you constantly see them (fleas/lice?) collecting on one another’s heads, I think you would be astonished if you could see them. Some of the men carry a bow and arrows and nearly all have at least two or three wives. Their idea of amusement at these gatherings is to make as much noise as they can with bells, flutes, horns etc and to dance, and while dancing they throw short poles at one another’s heels, constantly falling down of course. They bothered me a good deal as I was the only foreigner present, asking me all sorts of questions in bad Spanish. The “Gobernador” or Chief would persist in embracing me occasionally, but they did not molest me, a little too friendly, that was all. For two or three days, they kept up the feast, sleeping on the bare ground (there was no village or houses). The country people in Chiriquí, men and women alike, even if rich, go barefoot, though they think nothing of giving a sovereign for a straw hat, in which they are very extravagant. They are very fond indeed of dancing, and very often, especially on a moonlight night, in the dry season, they get up a “ball” or dance which they keep up the whole night; only one couple dance at a time, face to face, without touching one another, and when tired, another couple takes their place. The coffee business seems to be an utter failure (the price having gone down so much in London, New York, and Chiriquí), and nearly all my old friends on the slope of the Volcano are leaving to try their fortune elsewhere. The proprietor of Eureka failed and has gone back to Costa Rica, the same thing will happen, I expect, in Guatemala, the planters will be ruined. Here in David I always stay with a Frenchman; it seems almost like a home. I have stayed so many times in the house. Here I can leave all my heavy things while travelling; the family are always very kind to me; only wish there were such places to stay in Panama. There if you don’t go to the Grand Hotel and spend about £1 a day you have to live like a pig. I promised you a long letter and now have kept my word, my next will be short ones, will write on arrival at Panama. How I am going to get through my works in 2 months, I hardly know, the stay in Jamaica will probably have to be given up, and there is the trip from Colón to the Islands of Old Providence; anyway I ought to spend April in the Pearl Islands, and I ought to arrive in England about the end of May or beginning of June. Write care of the British Consul, Panama. The sailing vessel “Catalina” is to leave on the 12th, all being well ought to arrive at Panama about the 22nd. She is now loading with hides, rice, coconuts and coffee, she will also carry I expect about 50 pigs, and perhaps 8 or 10 passengers, where the latter will stow themselves, goodness only knows, one thing, it is the dry season. I remain Dear mother Your affectionate son George C. Champion

Wild mountains in Veraguas such as those through which GCC rode on his mule

Wild mountains in Veraguas such as those through which GCC rode on his mule