IN THE PUGMARKS OF CHAMPIONS

By James Champion

From September to December, 2006, I was engaged in a nostalgic tour of many of the former haunts of my grandfather, photographer and conservationist F. W. Champion. I managed to locate and photograph many of the scenes he had originally shot back in the 1920’s and 30’s, as well as to meet and interview many people who are carrying on the conservation battles that he helped initiate in those days long past.

F W Champion 1893 – 1970

As part of my research on FWC’s life and work, and on the legacy he left behind, I journeyed to India in September 2006 and spent three months travelling to many of the places frequented by him during his long stay in his beloved adopted homeland (1913 – 1947). My visit was facilitated by the Wildlife Institute of India and by the Forest Department (to whom I offer my sincerest thanks), and I had the privilege of meeting and learning from many of today’s most important wildlife conservationists, as well as talking with three veteran gentlemen who actually remembered him personally.

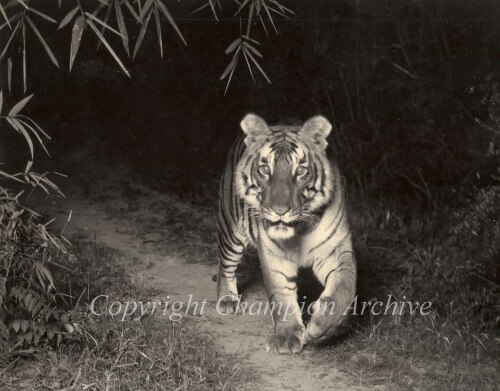

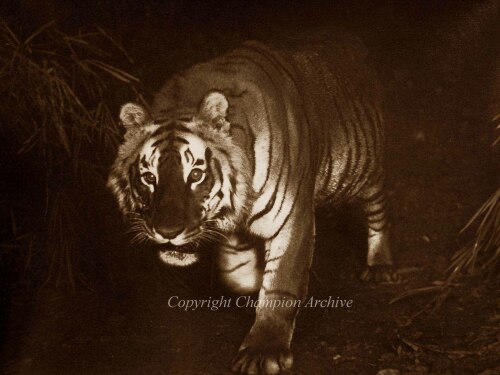

F. W. Champion OBE IFS was a forester with the Imperial Forestry Service, and a pioneering photographer and protector of tigers and other wildlife at a time when it was far more fashionable to look at a tiger down the barrel of a rifle than through the lens of a camera. Indeed he was one of the pioneers of the night-time flashlight photography system, whereby animals would trigger the camera and flash simultaneously, taking their own pictures – a modernised version of this system is still used by today’s wildlife researchers in their desperate quest to save India’s last tigers. I was privileged to meet Dr Bivash Pandav and Dr Abishek Harihar, both of the Wildlife Institute of India, who were engaged in camera-trapping in the Chilla range of the Rajaji National Park (see Sanctuary Asia magazine,Vol. XXVI No.5, October 2006). I was able to join them on a tour of what was one of FWC’s favourite haunts, and the situation there in the Park looked positive, despite the huge changes that have occurred since FWC trod these paths with his camera. Much progress has been made in recent years, but in Rajaji the potential tiger habitat is still fragmented due to the hydro-electric power channel and the main Haridwar – Rishikesh road, with both cutting across the narrow Chilla-Motichur Corridor which links the two halves of the Park.

As well as writing two books (With a Camera in Tiger-land, 1927, and The Jungle in Sunlight and Shadow, 1932, both published by Chatto & Windus), FWC also wrote numerous articles for magazines, and his photographs appeared on the front of the Illustrated London News on several occasions. He was ably assisted in his writings by his wife Judy, who accompanied him on all of his tours and was deeply involved in his numerous photographic and wildlife conservation projects. He also made numerous 16mm films, which together with his still photographs and diaries form a unique record of the rich jungles, in those days still teeming with animal life. His photographic and film collection is now housed in the Natural History Museum in London.

F W Champion was a friend and mentor of the renowned hunter of man-eating tigers and leopards, Jim Corbett, and indeed it was he who encouraged Corbett to make less use of the rifle and more of the camera, a fact recorded by Corbett in his book “The Man-eaters of Kumaon”. Champion was also on the steering committee for the establishment of the Hailey, later Corbett, National Park, now one of India’s premier tiger reserves and an important bastion against the immense poaching pressure that the tigers are currently facing. Here much valuable work is being done to maintain a healthy population of the great cats, as well as in building up vital links between the Park and the local communities in and around it. The Park celebrated its seventieth anniversary in 2006, and it was a privilege for me to be able to visit it in that momentous year, looked after by the Director Mr Rajiv Bhartari.

Among the many wonderful experiences I had during my action-packed four months, a few stand out particularly vividly in my memory: having the great fortune to see four tigers in five days in the Corbett National Park, with the uncanny thought that these magnificent animals might well be the descendents of those photographed back in the 1920’s or 30’s by my grandfather; recreating treks made by my great grandfather in 1894 and by my grandparents in 1936 to the remarkable disappearing Gohna Lake in Garhwal; accompanying my father to the very house in which he was born in Lansdowne, where his grandfather was Colonel of the Royal Garhwal Rifles regiment; finding F W Champion’s favourite wooden yacht “Stella” still in use at the Naini Tal Yacht Club; and watching a mother Great Indian Rhinoceros with her calf from the back of an elephant in the Dudhwa National Park, where my grandfather had been as Divisional Forest Officer and later Conservator of Forests.

As well as writing two books (With a Camera in Tiger-land, 1927, and The Jungle in Sunlight and Shadow, 1932, both published by Chatto & Windus), FWC also wrote numerous articles for magazines, and his photographs appeared on the front of the Illustrated London News on several occasions. He was ably assisted in his writings by his wife Judy, who accompanied him on all of his tours and was deeply involved in his numerous photographic and wildlife conservation projects. He also made numerous 16mm films, which together with his still photographs and diaries form a unique record of the rich jungles, in those days still teeming with animal life. His photographic and film collection is now housed in the Natural History Museum in London.

F W Champion was a friend and mentor of the renowned hunter of man-eating tigers and leopards, Jim Corbett, and indeed it was he who encouraged Corbett to make less use of the rifle and more of the camera, a fact recorded by Corbett in his book “The Man-eaters of Kumaon”. Champion was also on the steering committee for the establishment of the Hailey, later Corbett, National Park, now one of India’s premier tiger reserves and an important bastion against the immense poaching pressure that the tigers are currently facing. Here much valuable work is being done to maintain a healthy population of the great cats, as well as in building up vital links between the Park and the local communities in and around it. The Park celebrated its seventieth anniversary in 2006, and it was a privilege for me to be able to visit it in that momentous year, looked after by the Director Mr Rajiv Bhartari.

Among the many wonderful experiences I had during my action-packed four months, a few stand out particularly vividly in my memory: having the great fortune to see four tigers in five days in the Corbett National Park, with the uncanny thought that these magnificent animals might well be the descendents of those photographed back in the 1920’s or 30’s by my grandfather; recreating treks made by my great grandfather in 1894 and by my grandparents in 1936 to the remarkable disappearing Gohna Lake in Garhwal; accompanying my father to the very house in which he was born in Lansdowne, where his grandfather was Colonel of the Royal Garhwal Rifles regiment; finding F W Champion’s favourite wooden yacht “Stella” still in use at the Naini Tal Yacht Club; and watching a mother Great Indian Rhinoceros with her calf from the back of an elephant in the Dudhwa National Park, where my grandfather had been as Divisional Forest Officer and later Conservator of Forests.

At Dudhwa, I was able to make the acquaintance of two veteran gentlemen who actually had personal memories of FWC: Mr Billy Arjan Singh, the great “honorary tiger” and a man who truly earned the title “Champion of Tigers”, and Mr John Wakefield, then aged 91 and still working as Brand Manager of a resort in South India. John Wakefield, as owner of a shikar company, used to apply to FWC, then Divisional Forest Officer (DFO), for his shooting permits – FWC used to secretly tell his family that he would often issue permits to shoot in areas where he knew that his beloved tigers were absent!

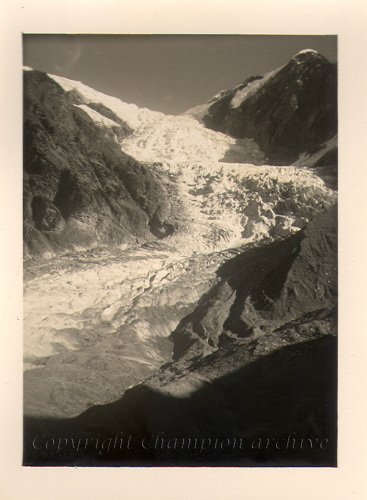

PINDARI GLACIER:

“Pindari”. The name had always held a fascination for me, knowing the remarkable links my family had had with this mighty glacier since 70 years ago. I grew up with the diaries and photographs that my grandfather and his party had kept, recording their trek into these remote Himalayan valleys in October 1936. An idea sprang to mind: October 1936/October 2006, an important anniversary; why not recreate their epic journey, staying in the same bungalows in the same villages on the same days, 70 years later, and record the dramatic changes that have taken place since then? And so it was that I found myself setting off with a group of friends and experts from The Wildlife Institute of India and the Uttaranchal Forest Department on the very same day that my grandfather’s group had set off all those years before.

This Pindari trek was a real highlight. I was able to recreate this journey precisely, using both the photographs and the diaries kept by by my father’s governess Kay Perry. She had accompanied my grandfather, my grandmother and my father, then aged 8, and recorded many details meticulously. I stayed in the same bungalows on the same nights, and photographed the same views from the same angles. The great mountains themselves have of course changed little over the decades, but the Pindari Glacier, when compared with my grandfather’s 1936 photograph, is but a shadow of its former self, having receded by more than two thirds due to the higher temperatures we are currently experiencing.

One incomparable experience was to find that an old shikari named Gopal Singh, who had guided my grandfather’s party to the glacier in 1936, had kept a register in which many early travellers had recorded their thanks for his excellent guiding. It turned out that this faded tome had been lovingly treasured in the village of Khati by Gopal Singh’s family, and to look at my grandfather’s hand-written entry from 9 October 1936 on 9 October 2006 in the company of Gopal Singh’s son-in-law and grandson, in Khati, was indeed uniquely moving!

Now that my research is over, I am back at work, but my mind strays ahead to the jungles and mountains of India, where I intend to return as soon as possible, hopefully to make a television documentary about my grandfather’s work, and the valiant efforts being made by today’s conservationists in their bid to save the forests of India and their denizens for the benefit of future generations.

How much more of the once proud Pindari Glacier will have melted away? And how many more of the few descendants of the magnificent tigers that my grandfather loved so much will have been poached, their skins and body-parts smuggled over the border into Nepal or Tibet, destined for the booming trade in wildlife products in the newly rich China? Will the authorities in India rise to the challenge of protecting these magnificent beasts, or will these tigers fade into our collective memory, victims of human greed and apathy? That remains to be seen, but I left the country with a feeling of optimism, having met so many passionate and dedicated people who are working hard to continue the work that my grandfather had started. I wish them every success in this vital task.